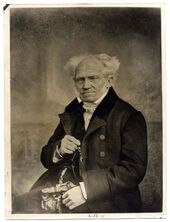

Arthur Schopenhauer

| Name: | Arthur Schopenhauer |

| Date of Birth: | February 22, 1788 |

| Occupation: | Philosopher |

| Ethnicity: | German |

| IQ: | Very high |

| RS: | 2[1] |

Arthur Schopenhauer was a post-Kantian, pessimistic German philosopher (born in 1788 in the city of Danzig, Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania, modern day Gdansk, Poland) and NEET. Though largely unappreciated in his own era, his writings had later become immensely influential. Of greatest relevance to this wiki, he is also known for his 'misogynist' essay entitled "On Women", which argued for female subordination, authored in 1851 in his books Parerga and Paralipomena.

Schopenhauer was not an incel. He had various love affairs throughout his life, not rarely with women much younger than him. He never married because he perceived monogamy as too limiting, so he was more of a Chad style misogynist than an incel misogynist; he was, however, mercilessly rejected by a 17 year old girl when he was 43. His work has been cited as a precursor to the blackpill philosophy,[2] though different from contemporary incel blackpillers, he did not even advocate against courtship, saying the lack thereof would drive people into boredom and suicide.[3]

On Women[edit | edit source]

Schopenhauer's essay On Women[4] concerns his disdain with what he perceived as the undue moral elevation of woman in the European society of his own time. Like Nietzsche (who was clearly influenced in his own view of women by Schopenhauer's writings), he perceived the treatment of women in the East, such as China and the Islamic world, as more just and in accordance with reason than the contemporary Western view of the role of women in society, which he viewed as originating in soppy French medieval chivalric texts. He claimed the veneration of women he saw in his own time was the "highest product of Christian–Teutonic stupidity".

He (like Aristotle before him) viewed women as chiefly representing stunted and imperfect males. In Schopenhauer's view, they are only destined for breeding and housekeeping, though he did later say that women who had the force of will and talent to "transcend" the limitations of their own sex could be viewed as worthy.

Schopenhauer continually portrays women as petty, childish, quarrelsome, frivolous, immoral, deceitful, and as being (altogether) the moral, intellectual and physical inferiors of man. He does, however, see women as being more pragmatic and realistic than men, but he attributes this mainly to what he sees as their greater materialism and lack of idealism. He states that women's fundamental flaw is their lack of justice, which he attributed to their deficiency of reasoning and also them being adapted by nature to rely on guile (namely their manipulation of men), rather than strength and intellect, to achieve their ends.

He concludes the essay by criticizing the institution of monogamy (which he, in any case, views as a falsity, arguing that polygyny is the natural state of man), saying this institution causes a surplus of unmarried women (who would rather live polygynously than entering a monogamous marriage), who then either become useless unhappy maids or overworked prostitutes, depending on their economic standing. He thus calls for the widespread legalization and implementation of polygamy in Europe, praising the Mormon's (at the time) practice of polygamy. He also calls for women to lose many of their legal rights, such as inheritance of property of their partners or fathers, or indeed legal guardianship over their children, with Schopenhauer arguing that women are mere children themselves who will always squander their late husbands wealth on mere vanities. He argues that women should not be guardians of children, as they themselves are dependents that require a guardian.

Quotes[edit | edit source]

The nobler and more perfect a thing is, the later and slower is it in reaching maturity. Man reaches the maturity of his reasoning and mental faculties scarcely before he is eight-and-twenty; woman when she is eighteen; but hers is reason of very narrow limitations. This is why women remain children all their lives, for they always see only what is near at hand, cling to the present, take the appearance of a thing for reality, and prefer trifling matters to the most important.

Women are directly adapted to act as the nurses and educators of our early childhood, for the simple reason that they themselves are childish, foolish, and short-sighted—in a word, are big children all their lives, something intermediate between the child and the man, who is a man in the strict sense of the word.

For as lions are furnished with claws and teeth, elephants with tusks, boars with fangs, bulls with horns, and the cuttlefish with its dark, inky fluid, so Nature has provided woman for her protection and defence with the faculty of dissimulation [..] Hence, dissimulation is innate in woman and almost as characteristic of the very stupid as of the clever. Accordingly, it is as natural for women to dissemble at every opportunity as it is for those animals to turn to their weapons when they are attacked; and they feel in doing so that in a certain measure they are only making use of their rights.

"It is only the man whose intellect is clouded by his sexual instinct that could give that stunted, narrow-shouldered, broad-hipped, and short-legged race the name of the fair sex; for the entire beauty of the sex is based on this instinct. One would be more justified in calling them the unaesthetic sex than the beautiful. Neither for music, nor for poetry, nor for fine art have they any real or true sense and susceptibility, and it is mere mockery on their part, in their desire to please, if they affect any such thing.

Because women in truth exist entirely for the propagation of the race, and their destiny ends here, they live more for the species than for the individual, and in their hearts take the affairs of the species more seriously than those of the individual. This gives to their whole being and character a certain frivolousness, and altogether a certain tendency which is fundamentally different from that of man; and this it is which develops that discord in married life which is so prevalent and almost the normal state."

They are the sexus sequior, the second sex in every respect, therefore their weaknesses should be spared, but to treat women with extreme reverence is ridiculous, and lowers us in their own eyes [...] And it was in this light that the ancients and people of the East regarded woman; they recognised her true position better than we, with our old French ideas of gallantry and absurd veneration, that highest product of Christian–Teutonic stupidity.

Getting married means doing what is possible to disgust one another. [...] halve one's rights and double one's duties. […] Getting married means reaching into a sack blindfolded and hoping that you can find an eel out of a bunch of snakes.

Schopenhauer was redpilled on the wall:

On the whole, it is effective from the years of beginning to those of ending menstruation. However, we give decided preference to the period from the eighteenth to the twenty-eighth year. Outside of those years, no woman can excite us; an old woman arouses our disgust. Youth without beauty, still has its charm; beauty without youth, none.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ https://theodora.com/encyclopedia/s/arthur_schopenhauer.html

- ↑ https://multiversityproject.co/blog/did-incels-get-their-philosophy-from-schopenhauer/

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Romance_(love)&oldid=1035315905#Arthur_Schopenhauer

- ↑ https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Studies_in_Pessimism/On_Women