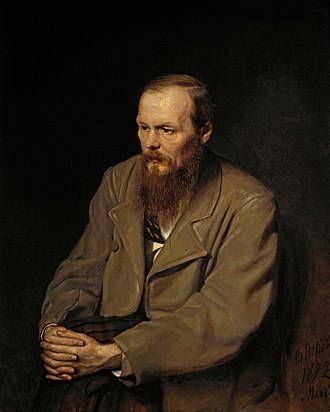

Fyodor Dostoevsky

| Name: | Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky |

| Date of Birth: | November 11th 1821 |

| Occupation: | Writer |

| Ethnicity: | Russian |

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821 – 1881) was among the most important Russian philosophers and authors of all time. He was an observer of the conflicts that agitated humanity at the dawn of modernity and a central theme in his works was the human soul whose movements, constraints, and liberations he explored impressively through literature. Friedrich Nietzsche called him "the only psychologist from whom I had something to learn" in Twilight of the Idols, one of his final works before suffering a mental collapse.

Some of his works are filled with Simps, Whores, Soys, cuckmaxxed Cucks and related member of soyciety.

Life[edit | edit source]

Born in Moscow; educated as an engineer but turned to literature. Arrested in 1849 for membership in the revolutionary Petrashevsky Circle, sentenced to death, then reprieved at the last moment and sent to an Siberian penal servitude for 4 years followed by military exile. After returning to St. Petersburg he produced his major psychological novels - Notes from Underground, Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, Demons, and The Brothers Karamazov - while battling epilepsy, a crippling gambling addiction, chronic financial trouble, and personal loss. His life experience (religious upbringing, imprisonment, illness, and hardship) shaped fiction that relentlessly examines guilt, free will, faith, suffering, and the depths of the human soul. While his contemporaries Leo Tolstoy, Ivan Turgenev and Ivan Goncharov were able to write in conditions of material comfort, the external circumstances of Dostoyevsky's writing career were marked by financial hardship for most of his life. Only in the last ten years of his life, he lived in financial stability and enjoyed recognition throughout the country.

Non-Protocel Life and First Signs of Cuck-akin Betabux Behavior[edit | edit source]

He wasn't a Protocel, married twice and had sex prior death: During a visit, Dostoevsky met the single mother foid Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva, fell in love with her and betabuxxed as Isaeva and her son later moved to him. They married in 1857, even though she had initially refused his marriage proposal, stating that they were not meant for each other and that his poor financial situation precluded marriage. Their family life was unhappy and she found it difficult to cope with his seizures. They mostly lived apart. Describing their relationship, he wrote: "Because of her strange, suspicious and fantastic character, we were definitely not happy together, but we could not stop loving each other; and the more unhappy we were, the more attached to each other we became". In 1864, Maria died.

People's Comments on his Appearance[edit | edit source]

"[Dostoevsky] looked morose. His sickly, pale face was covered with freckles, and his blond hair was cut short. He was a little over average height and looked at me intensely with his sharp, grey-blue eyes. It was as if he were trying to look into my soul and discover what kind of man I was." - Baron Alexander Egorovich Wrangel

Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina, his 2nd wife, remarked that he was of average height but always tried to carry himself erect:

"He had light brown, slightly reddish hair, he used some hair conditioner, and he combed his hair in a diligent way ... his eyes, they were different: one was dark brown; in the other, the pupil was so big that you could not see its color, [this was caused by an injury]. The strangeness of his eyes gave Dostoyevsky some mysterious appearance. His face was pale, and it looked unhealthy."

Works[edit | edit source]

White Nights (1848)[edit | edit source]

The nameless Simp, "the Dreamer", is an isolated, socially awkward, quiet young man who wanders the "white nights" of St. Petersburg and saves the foid Nastenka (Anastasia) from harassment by a drunk beta. Then, over four nights, they share their life stories: The Dreamer confesses he has never spoken to people, only lived in his imagination, while Nastenka reveals she is waiting for her lover to return. Her lover (Chad) promised to return for her in a year (It’s been a year, and she is waiting each night for him to show up at the appointed place). When he fails to do so on the 2nd night, the soy-ish Dreamer offers to help Nastenka send a letter to him through intermediaries. On the 3rd night, Nastenka and even the already semi-cucked Dreamer are upset when he neither reappears nor sends a return letter. The Dreamer falls in love with Nastenka despite her clear warnings not to fall in love with her (though, he doesn't understand that Nastenka’s openness with him is less about affection and more about her own loneliness after being dumped by Chad). When she starts comparing him favorably, he hopes that she might be falling in love with him instead.

The next day and night are rainy, so although the Dreamer waits by the canal as usual, Nastenka fails to appear. But on the following night, Nastenka is at the canal before the Dreamer. There is still no sign of Chad, and she concludes that he must not love her any longer. The Dreamer comforts her and offers to love her forever, even if her heart is already committed to the new lodger. She accepts his offer gratefully, and they giddily begin to imagine their lives together. But then, Chad appears out of nowhere and Nastenka flies instantly back into his arms (Brutal). The following day, the Dreamer gets a letter from Nastenka in which she says that she'll marry Chad within the week. She thanks the Dreamer for everything he did for her during her agonizing wait, she begs his forgiveness for breaking his heart, and she expresses her hope that they can still be friends. He doesn’t answer the letter. But neither does he ever forget Nastenka, whom he still loves, pines for, and remembers fondly in his daydreams even 15 years later, leaving the narrator heartbroken but he copes by being grateful for the brief moment of connection.

Dear Filmcels, Here you can find the Russian Film version with English Subtitles.

Notes From the Underground (1864)[edit | edit source]

The novel presents itself as an excerpt from the memoirs of a bitter, isolated, unnamed narrator (generally referred to by critics as the Underground Man), who is a retired civil servant living in St. Petersburg.

Author's note: "The author of the diary and the diary itself are, of course, imaginary. Nevertheless it is clear that such persons as the writer of these notes not only may, but positively must, exist in our society, when we consider the circumstances in the midst of which our society is formed. I have tried to expose to the view of the public more distinctly than is commonly done, one of the characters oft he recent past. He is one of the representatives of a generation still living. In this fragment, entitled ‘Underground,’this person introduces himself and his views, and, as it were, tries to explain the causes owing to which he has made hisappearance and was bound to make hisappearance in our midst. In the second fragment there are added the actual notes of this person concerning certain events in his life."

Synposis[edit | edit source]

Notes from Underground is divided into two sections. The first, “Underground,” is shorter and set in the 1860s, when the Underground Man is forty years old. This section serves as an introduction to the character of the Underground Man, explaining his theories about his antagonistic position toward society:

The first words we hear from the Underground Man tell us that he is “a sick man . . . a wicked man . . . an unattractive man” whose self-loathing and spite has crippled and corrupted him. He is a well-read and highly intelligent man, and he believes that this fact accounts for his misery. The Underground Man explains that, in modern society, all conscious and educated men should be as miserable as he is. He has become disillusioned with all philosophy. He has appreciation for the sublime, Romantic idea of “the beautiful and lofty,” but he is aware of its absurdity in the context of his narrow, mundane existence.

He has great contempt for nineteenth-century utilitarianism (attempt to use mathematical formulas and logical proofs to align man’s desires with his best interests) and complains that man’s primary desire is to exercise his free will, whether or not it is in his best interests: In the face of utilitarianism, man will do nasty and unproductive things simply to prove that his free will is unpredictable and therefore completely free. This assertion partially explains the Underground Man’s insistence that he takes pleasure in his own toothaches or liver pains: such pleasure in pain is a way of spiting the comfortable predictability of life in modern society, which accepts without question the value of going to the doctor. The Underground Man is not proud of all this useless behavior, however. He has enormous contempt for himself as a human being. He is aware that he is so overcome by inertia that he cannot even become wicked enough to be a scoundrel, or insignificant enough to be an insect, or lazy enough to be a true lazybones.

The second fragment “Apropos of the Wet Snow” describes specific events in the Underground Man’s life in the 1840s, when he was twenty-four years old. In a sense, this section serves as a practical illustration of the more abstract ideas the Underground Man sets forth in the first section. This second section reveals the narrator’s progression from his youthful perspective, influenced by Romanticism and ideals of “the beautiful and lofty,” to his mature perspective in 1860, which is purely cynical about beauty, loftiness, and literariness in general. It describes interactions between the Underground Man and various people who inhabit his world: soldiers, former schoolmates, and prostitutes. The Underground Man is so alienated from these people that he is completely incapable of normal interaction with them. He treats them with a mixture of disgust and fear that results in his own effacement or humiliation, which in turn result in remorse and self-loathing.

The Underground Man’s alienation manifests itself in all kinds of relationships. When walking in the park, he obsesses about whether to yield the right of way to a soldier whom he does not even know. Then, in a confused attempt at social interaction, he deliberately follows some school acquaintances to a dinner where he is not wanted, alternately insulting them openly and craving their attention and friendship.

Later that same evening, the Underground Man attempts to rescue an attractive young prostitute named Liza by delivering impassioned, sentimental speeches about the terrible fate that awaits her if she continues to sell her body after sleeping with her at a brothel. Liza is somewhat "shy/innocent" despite her profession, and she responds emotionally to his efforts to convince her of the error of her ways. She is naturally loving and sympathetic, but she also has a (probably faked) sense of pride and nobility. When Liza comes to visit the Underground Man in his shoddy apartment several days later, he reacts with shame and anger when he realizes she has reason to pity or look down upon him. He continues to insult Liza throughout the visit. Hurt and confused, she leaves him alone in his apartment.

Here, the notes end. In a footnote at the end of the novel, Dostoevsky reveals that the Underground Man fails to make even this simple decision to stop writing, as Dostoevsky says that the manuscript of the notes goes on for many pages beyond the point at which he has chosen to cut it off.

Selected Quotes[edit | edit source]

“I am a sick man.... I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man."

"Now, I am living out my life in my corner, taunting myself with the spiteful and useless consolation that an intelligent man cannot become anything seriously, and it is only the fool who becomes anything. Yes, a man in the nineteenth century must and morally ought to be pre-eminently a characterless creature; a man of character, an active man is pre-eminently a limited creature."

“I hated my face, for example, found it odious, and even suspected that there was some mean expression in it, and therefore every time I came to work I made a painful effort to carry myself as independently as possible, and to express as much nobility as possible with my face. "let it not be a beautiful face," I thought, "but, to make up for that, let it be a noble, an expressive, and, above all, an extremely intelligent one." Yet I knew, with certainty and suffering, that i would never be able to express all those perfections with the face I had. The most terrible thing was that I found it positively stupid. And I would have been quite satisfied with intelligence. Let's even say I would even have agreed to a mean expression, provided only that at the same time my face be found terribly intelligent.”

“Oh, gentlemen, perhaps I really regard myself as an intelligent man only because throughout my entire life I’ve never been able to start or finish anything.”

"I swear, gentlemen, that to be too conscious is an illness - a real thorough-going illness"

"To love is to suffer and there can be no love otherwise."

"I say let the world go to hell, but I should always have my tea."

"How can a man of consciousness have the slightest respect for himself."

"in despair there are the most intense enjoyments, especially when one is very acutely conscious of the hopelessness of one's position."

"To care only for well-being seems to me positively ill-bred. Whether it’s good or bad, it is sometimes very pleasant, too, to smash things."

“You see, gentlemen, reason is an excellent thing, there’s no disputing that, but reason is nothing but reason and satisfies only the rational side of man’s nature, while will is a manifestation of the whole life, that is, of the whole human life including reason and all the impulses. ”

"At that time I was only twenty-four years old. My life then was already gloomy, disorderly, and solitary to the point of savagery."

Reception[edit | edit source]

Mike Crumplar considers Elliot Rodger's manifesto "My Twisted World" a serious work of literature and compares it to Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground. He believes that Dostoevsky might compare Elliot Rodger to a Jesus figure, and would cite Elliot as 'crucified by Americans'. He believes Elliot Rodger was a byproduct of 'a racist and inegalitarian society'.

There's an okay-ish Americanized Film Version of it, too

The Eternal Husband (1870)[edit | edit source]

Velchaninov, suffering from hypochondria and guilt over past affairs, is tracked down by Trusotsky who behaves erratically alternating between friendly affection and sinister hostility. Trusotsky brings with him a young girl, Liza, whom Velchaninov realizes is his biological daughter from his affair with Trusotsky's late dead wife (Concerned for his biological daughter, Velchaninov later takes her away from the seemingly unstable Trusotsky, but she ultimately dies while in foster care). Velchaninov invites Trusotsky to his apartment under the guise of friendship. However, beneath the surface, a psychological duel unfolds: Trusotsky oscillates between pathetic victim and cunning manipulator. His obsessive behavior and subtle provocations unsettle Velchaninov, who grapples with guilt and confusion. Through a series of conversations and confrontations, Trusotsky discloses disturbing insights into Natalia’s infidelity and mental state before her death. Velchaninov confronts his own moral failings and the consequences of his past actions. Velchaninov coins the term "eternal husband" for Trusotsky, describing a man whose sole role is to be a husband, even while knowing about his wife’s infidelity. Trusotsky attempts to remarry, seeking a new teen bride, but is rejected, further fueling his rage. After a failed attempt to kill Velchaninov with a razor in a drunken rage, Trusotsky departs. The story ends with the two men meeting again at a railway station, appearing to have returned to a state of polite, superficial acquaintanceship, yet both forever changed by the psychological battle.